Is It Possible to Learn This Power?

Realizing you have tunnel vision is tough, and shaking that feeling off can be even harder. That’s why I decided to confront what I saw as a weakness in my thinking pattern, and for me, it was represented as a chess game.

In tech, specialization is essential—it’s what makes you effective. But it also forces you to focus intensely on one “column,” leaving you vulnerable to problems outside that scope. You’re like a rocket: capable of extraordinary things when aimed in the right direction, but prone to disaster without the help of others to steer you clear of obstacles. Back then, I couldn’t see those obstacles—that’s tunnel vision in action.

Back then, I noticed that Tech Managers and Directors didn’t seem to suffer from this (at least, not visibly). Their broader perspective allowed them to anticipate and predict moves on the chessboard. While it sounds obvious in theory, putting it into practice is an entirely different challenge.

Long story short, I found a way to break free by blending different techniques and strategies. Now, in a better position, I can’t help but think about those who are still stuck seeing only a few squares ahead. How can I share the mindset and tools I’ve gained to save them a few years—or at least spare them a few headaches?

Instead of focusing on just 2–3 squares ahead, I want others to see 7–8. At the very least, I want you to develop the ability to see the side view of at least one square, broadening your perspective.

If people can achieve that level of awareness, it will make my life so much easier. I could rely on others more effectively, rather than feeling like I have to bring out a nuke to solve every problem.

In a world dominated by systems, navigating through them is far more important than the speed at which you move through them. Looking back, to survive my trials in a big company, adapting was the number one priority.

But the key word shouldn’t be “adapting” then? Nope, that’s a subproduct of the technique that I apply.

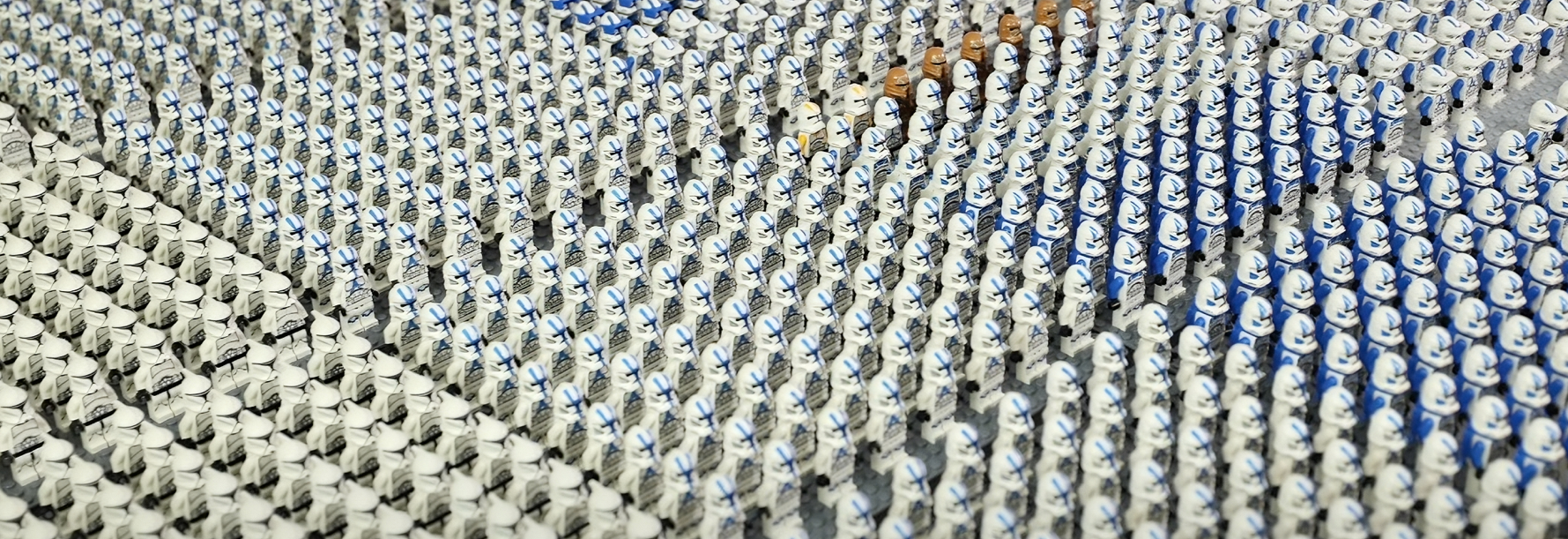

The concept of mapping came back to me a year ago when I had to explain the problems derivated from the inner workings of systems and their interconnections to a client. These were elements I could clearly see, but they struggled to grasp. Interestingly, I managed to convey this through LEGO. Thought it wasn’t the LEGO itself that was indispensable—it was the root of my ability to visualize. Like imagining, but with structure. Tying things together in a way that makes sense and show that mental map to others.

For me, this process feels automatic. Maybe it’s part of my education, or maybe it’s the years spent playing with LEGOs—building characters, connections, and stories. It’s the same mental framework I use today, just with a company variable instead of plastic bricks.

I can teach a lot from my experience or by leading through example, but instilling a way of thinking—that’s the real challenge.

For me, teaching is an exchange. I’m upfront about what I expect, and among all the things I could ask for, loyalty or personal appreciation isn’t one of them.

I’ve developed a sense for recognizing when someone is open to learning and when they simply don’t care. Naturally, I choose to invest my time in those who are willing to grow. But it’s never one-sided—I learn just as much from their perspectives. It’s not just about technical skills; attitudes, mannerisms, opinions, even memes—everything adds up and shapes the way I see things.

Above all, I do it because I want to. It’s what others did for me when I needed it, and I see it as my way of paying it forward. And no, I wouldn’t put a paywall on that—at least not an expensive one, jaja.

So my wish for the people that I work with is not for them to be tied to me, if they want to stick great, but I’ll be even happier to now that they are carving their own path and moving forward in the way that they can.

I’m also tired of hearing, “We need to hire clones of you.” That would be awful. Unless there’s diversity in thought and skills, a team of clones would be the worst outcome. Sure, we’d get from point A to B quickly—or even find a shortcut to C. But the moment things change, or we need to explore new ideas, the lack of variation would hold us back. That’s why investing time in people is a better approach.

Yes, it’s expensive. But out of 100 people, if even one does something meaningful—whether it’s work they’re proud of or helping others—that investment is worth it. I’m not talking about inventing revolutionary technologies, but creating something that matters, even in small ways.

If you’re still not convinced why this is important, let me put it this way: moving up in your career will require you to rely on others. Your performance will increasingly depend on their efforts. Sooner or later, you’ll need to trust and count on people. I keep my expectations realistic, but I also know I can’t be everywhere at once. If I’m unable to handle my part, I need someone I trust to step in.

This isn’t about heroism or savior complexes—I’ve made my peace with those ideas. It’s about freedom. Freedom to rely on others, to let them shine, and to avoid a culture of dependency on one “indispensable” individual. If I were running a company, I wouldn’t want someone who believed they were irreplaceable. Trust is essential, but symbiotic dependency is dangerous.

I know it might sound like overthinking for something that should just involve running commands and troubleshooting. But sadly, it’s rarely that simple. There’s always more at play—business pressures, relationships, team dynamics, and external factors all add layers of complexity.